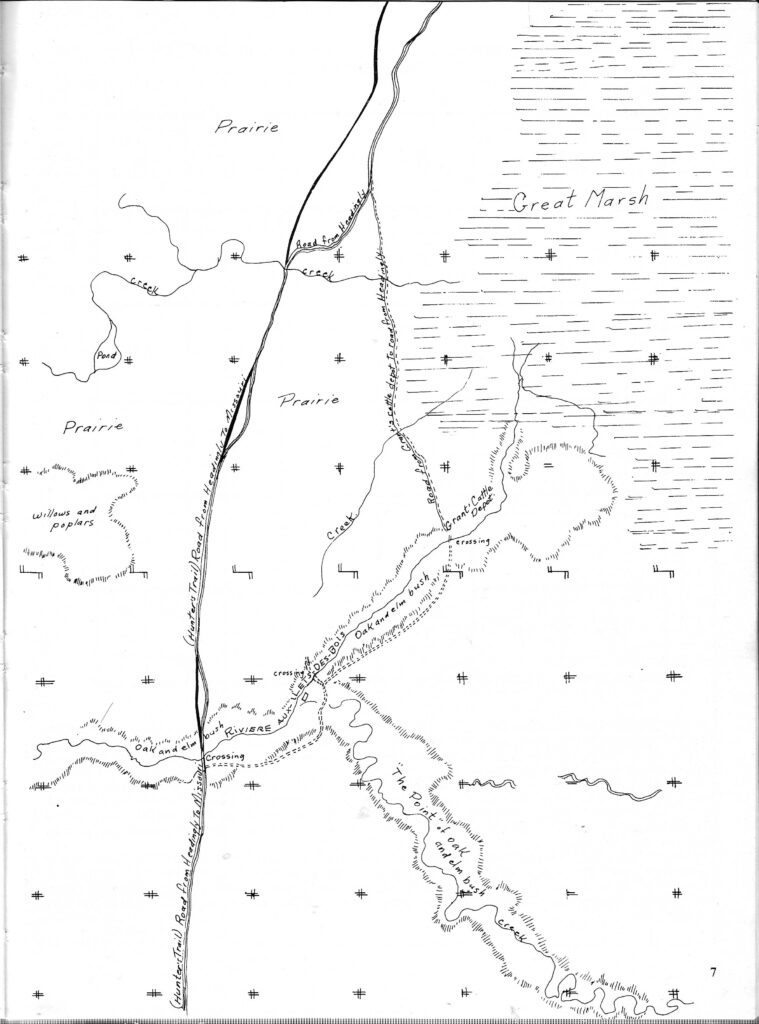

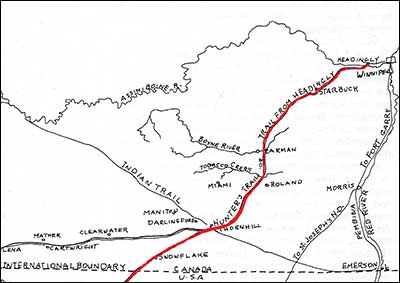

The Missouri Trail2 was the major pathway followed by early Indigenous peoples, on their way to gather and trade at the junction of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers in the north and the headwaters of the Missouri River to the south. It was the route to the sacred site at Calf Mountain and the pathway later used by fur traders and buffalo hunters. The trail followed the western shore of the Great Marsh, passing through miles of swampy land and open prairie before crossing the river about a mile and a half east of present-day Carman. The wooded crossing provided an oasis where travellers found water, food, and fuel as well as wood for repairing their Red River carts. In springtime, maple syrup was harvested. By the 1830s, a number of Métis families were living in the area. The name they gave to the river was the Rivière aux Îlets-de-Bois (‘islands of wood’), possibly a translation of an earlier Indigenous name.

Most of our local written histories date from the 1870s. This leaves a huge gap in our knowledge and understanding of the earlier centuries of Indigenous interaction with the river, making it a part of our heritage that remains largely unrecorded and unrecognized. We know from a large volume of other oral histories and Indigenous writings that water, as a giver of life, was sacred, that it held a central, spiritual place in Indigenous cultural belief systems.3 We can only hope that local oral history projects will capture some knowledge and understanding of these beliefs and their significance to the river’s story.

The trail skirted the western edge of the Great Marsh from the Headingley area, angling southwest past what would later become the Boyne Settlement, eventually giving access to the Missouri River. The trail was used by early explorers, fur trading companies, buffalo hunters and later by settlers to the area.

The trail crossed the Boyne River about a half mile east of present-day Carman, following the route of what is now Highway #3 south across Tobacco creek and angling southwest to what would become the settlement of Nelsonville, which was then in Dufferin. A.P. Stevenson, (Farmer’s Advocate, Jan. 4, 1911) described the route as settlers saw it: “ .. In the spring of 1874, in company with five others with ox and cart to carry provisions, I started to Pembina Mountain to look for land. The old Missouri trail was followed between Headingly and La Salle River near Starbuck. Nearly two-thirds of the way was through swamps, with water two or three feet deep. The ox and carts were mired three or four times, and what a delightful time we greenhorns had, up to the waist in water, with millions of mosquitoes adding their notes to the proceedings. It was a hungry, tired crowd that camped that night on the dry banks of the high-smelling La Salle, trying to dry socks, etc. Our clothing had early in the day been made up into bundles and tied high and dry on our backs during passage of the swamps. The following morning we found our ox had broken loose and taken the road to the Boyne River, so we started on foot for the same place. The distance was 30 miles, a dead level plain, without a tree, shrub or twig, no house of any description, not a drop of water to drink.”

It was this route that led John Grant to settle in the area and for homesteaders to claim land around what became the Boyne Settlement. A sign was erected in 1960 by the Carman/Dufferin Municipal Heritage Advisory Committee (C/D MHAC) to mark the point where the Missouri trail crossed Highway #3; it was later removed by the landowner. C/D MHAC made a replacement of the sign and did further research on pre-1870 history of the Trail the focus of 2020 Manitoba 150 celebrations in this area.

February 2018

Missouri or Hunters’ Trail. A sub-committee under the capable guidance of Debbie Nicolajsen is working on a proposal to reinstall a monument marking the place where the Trail once crossed the Boyne River in the R.M. of Dufferin, about a mile and a half east of the Town of Carman. The original sign was put up in 1961 by the Dufferin Historical Society but later removed by a landowner.

The Trail is of historical interest to all Manitobans because, for centuries, it formed the pathway for buffalo herds, Indigenous tribes, fur traders and buffalo hunters from the junction of the Red and Assiniboine rivers to what later became the south-western part of the Province and northern U.S.A. From the birth of Manitoba in 1870 until the arrival of the railways 20 to 30 years later, it then became a major route through which settlers poured into the area to claim homestead lands.

Indentation still visible where the Missouri Trail crossed the Boyne River.

The challenge for Debbie and her team is to design a permanent, attractive marker, visible to passersby but not publically accessible because it will be on private property.

As well, they want to tell the fascinating story behind a trail whose last rutted traces across the R.M. are disappearing in the face of cultivation and development.

The committee has some neat ideas which will unfold between now and 2020, when we will celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Province. A big high-five to our volunteers!

July 2019

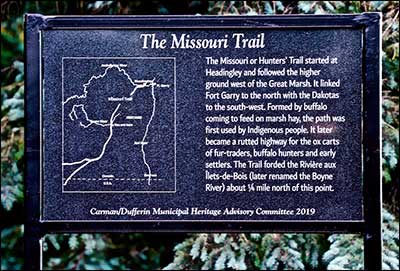

Missouri Trail sign. We are delighted at finally being able to announce that the new Missouri Trail sign has been installed. The sign marks the location where the trail once crossed the Rivière aux Îlets de Bois, now known as the Boyne River. For centuries, this historic pathway was used by buffalo coming to feed on swamp hay. Indigenous people followed the trail for trade and contact with other tribes or for travelling to sacred sites such as Calf Mountain near Darlingford.

In later years, it was used by fur traders to reach the Missouri and by buffalo hunters when the herds moved further southwest. After crossing miles of open prairie, the point where the trail crossed the river was important as a source for water, fuel, and wood to repair Red River carts.

Post-1870, the government opened Manitoba lands to homesteaders and granted land to men who had served in military expeditions. This marked the beginning of the socio-economic transformation of the area into a primarily farming community.

Early setters used the Missouri Trail to travel from the Red River settlement to this area and further south. The first settlers selected choice lands near the river where wood and water were abundant. Others settled in the Salterville area or fanned outward to claim homesteads in other parts of what is now the RM of Dufferin. As more families arrived, the demand grew for easier access to the area. By 1882, the railway to Barnsley became an arrival point for both new settlers and for the mail. Use of the trail declined.

Today, most of the land has been cultivated and the last traces of the deep ruts formed by the Red River carts have disappeared. In 1961, the Dufferin Historical Society placed a sign to mark this significant historic site. The sign was later removed by a landowner.

New black granite sign marking

location of the Missouri Trail.

Above, original wooden sign installed in 1961

by the Dufferin Historical Society. A map and

legend similar to the current sign were on the

back.

Replacing the sign has been a Carman/Dufferin MHAC priority for the past decade. Thanks to the diligent efforts of our members over the years, this has at last been accomplished. Ironically, it’s just in time for our celebration of the 1870 events that changed the course of local history and, in the process, marked the beginning of the end of the Missouri Trail as the major access route to this region.

The new sign features a diamond-cut map and legend on black granite and was crafted by Carman Granite. We are indebted to Debbie Nicolajsen for guiding the project these past months through the process of obtaining highway permits and caveats. Members of the community also have stepped forward with significant support. Special thanks to Lee and Lee, Barristers and Attorneys at Law for donating their legal services and to Sperling Industries for generously donating the metal framework for the sign. And, as always, Sharla Murray, CAO of the RM of Dufferin, has been a primary resource person for our work.

January 2020

Over the past months we have been trying to gain greater insight into local history of this during the pre- and post-1870 era. C/D MHAC members have researched the story of the Missouri Trailand re-installed a sign where the trail once crossed the Rivière-aux-Îlets-de-Bois (Boyne River).

February 2020

Lands, Trails and People

One of our first tasks this year is to arrange the unveiling of the newly re-installed Missouri Trail sign. A couple of years ago we asked our committee why they thought we should plan on re-installing the sign in time for 2020, the 150th anniversary of the province of Manitoba. The response was “because that’s how the first settlers reached the Carman area”. Since then we’ve asked others the same question, including the Wednesday Morning group; each time we get the same reply. That’s not at all surprising because most of the recorded history as we know it has been written by people who arrived after that time. We tend to see history through the lens of ‘our’ experience— in this case, the people who wrote existing accounts of local history. Most of the events and artifacts we’ve collected information about through our C/D MHAC projects fall into the same post-1870 category—our heritage buildings, stories of homesteads and early farms, inventories of resources from communities, vintage photographs.

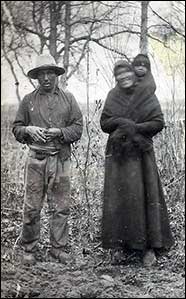

The history and heritage of earlier inhabitants of the area were handed down through the generations largely through oral tradition. Much of what we know is from artifacts in museums and recorded contacts with European explorers, traders and settlers. The only photograph of indigenous people we’ve seen so far in our collections of local photographs was taken by early photographer J.B. Coleman who documented the area around Roseisle in the early 1900s. His family homesteaded along the escarpment beside the local “Indian Trail” marked on early survey maps.

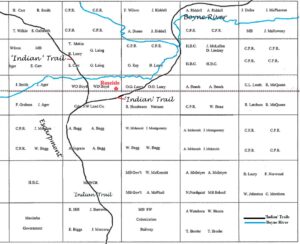

This trail along the escarpment was one of several that crossed what became known as the R.M. of Dufferin, an area extending from the escarpment in the west to the Great Marsh east of present-day Town of Carman. The most prominent of the trails was the Missouri or Hunters’ Trail.

Seen from a broader historical perspective, the Missouri Trail is a symbol of local pre-1870 history. The legend on the sign records that the Trail dates back a few centuries to the days when the hooves of migrating buffalo first carved out a pathway to the Great Marsh in search of grass and hay. Nomadic indigenous people followed their trail to hunt the buffalo that were essential at that time to their survival. Dried buffalo meat or pemmican was their staple winter food. They used the hides for clothing and tents, the sinews for thread, and bones for needles, tools. Indigenous groups are thought also to have followed the pathway to sacred sites at places like Calf Mountain and to meet with other tribes.

With the arrival of the fur trade, pemmican took on new significance as the main source of a light, portable source of nutrients for canoeists who paddled up to 14 hours a day and carried heavy loads across portages. The buffalo herds were found at that time south of Lake Manitoba and west of the Red River and this area became part of what has been described as the ‘larder’ of the fur trade.

In 1870, Métis made up a large percentage in the Red River settlement. Even though they lived for the most part on land claims, their main livelihood was as buffalo hunters and guides. They also were middleman in the fur trade between the fur agents and the native population because they knew the language and had connections through their Indigenous ties. The hooves of buffalo hunters’ horses and, after about 1806, the creaking wheels of Red River carts further defined the trail with deep grooves from passage of cart wheels. When Manitoba became a part of Canada in 1870, the land was surveyed into townships and sections and opened for homesteading. The Trail initially was the main pathway into this area.

The Trail wasn’t designed for bringing in settlers from the East and their belongings. A.P. Stevenson gave an account of his 1874 journey through swampy areas of the Trail where they were plagued by mosquitoes (see History of the RM of Dufferin, p.4). Within a decade, a railway was built to End-of-Line (Barnsley). It was extended to Carman in 1889 and by 1901, ran from the east through Homewood and other communities. New towns grew up along the rail line to the west. From this broader perspective, the importance of the Missouri Trail lay in the centuries before 1870. Arrival of settlers in effect marked the end of a trail that served as a pathway to and from the southwest. The Missouri Trail sign is not so much a tribute to the present agricultural community as it is a symbol of the rich early history of the territory that became known as Southwestern Manitoba and the Carman/Dufferin municipalities.

Further Reading:

The History of the R.M. of Dufferin in Manitoba 1880-1980, pp. 4-7

A Review of the Heritage Resources of Boyne Planning District, pp.97-101 a study by Karen Nicholson, Historic Resources Branch, November 1984.

Marking the Missouri or Hunters’ Trail

The unveiling was to have been a well-publicized event, originally scheduled for May12—until the pandemic arrived. With all the signs in place, the committee decided to go ahead on this alternate date with an unpublicized, scaled-down, social-distanced ceremony. For those of you would otherwise have attended, the best we can do is provide you with photographs and a full account of the event. Thanks to Bev MacLean who did a great job of preserving the event with these photos.

July 15, 2020 Unveiling Ceremony. The ceremony opened with a treaty acknowledgement delivered by Elaine Owen. This was followed by recognition of “the most important part of any project, the people who make it possible.”*

Mr. Blaine Pedersen, our hard-working and conscientious MLA for Midland, and Reeve George Gray, RM of Dufferin, a staunch supporter of local heritage, brought greetings respectively from the Province and the Councils of the RM of Dufferin and Town of Carman.

Transcript of proceedings from Missouri Trail sign unveiling ceremony

C/D MHAC Chair Ina Bramadat outlined why our committee chose the signs as our symbols of 1870. Each month in 2020, News & Events has featured one part of the background to the events of 1870. At the risk of giving away the plot of the story, here’s the full summary:

“It’s interesting when we’ve asked people, even some on our committee, why they think the Trail is important to our history, they invariably look at us as if it’s a trick question and reply “Because it’s how the first settlers arrived.” We’re fortunate in Carman/Dufferin to have a rich body of local history. However, most of it has been written since 1870 by our early settlers and their descendants and, like most histories, it reflects the experiences and viewpoint of those who lived it. But why was there a trail here for the settlers to use? Who made it and where did it go? Answer those questions and you get a sense of the depth of our local heritage and just how significant 1870 really was to this area. And you realize that in effect 1870 ushered in what was likely the most rapid and significant socio-economic and cultural change in local history.

If the Trail were to tell its own story, it would begin hundreds of years ago when large herds of bison, or buffalo as they were then known, carved a pathway as they came to feed on the hay of the Great Marsh that lay east of this area. The Plains people who lived here at that time lived by gathering and hunting. They depended on the buffalo for food, shelter, clothing, tools and for the dried meat or pemmican that meant their survival during the long winter months.

Indigenous bands also travelled southward along the trail, to visit the sacred mound at Calf Mountain and still further south to the headwaters of Missouri River, where they traded for corn and other agricultural products with the Mandan tribe and took part in the large ceremonial gatherings that were part of indigenous lifestyle.

By the time explorers from New France arrived here in the early 1600s the pathway would already have become a well-used trail. The explorers came searching for a western passage to the orient; they soon discovered that the real wealth of the land lay in northern furs. Over the next two centuries the fur trade became a dominant presence in the north-west. During this era, European goods such as metal utensils and cloth replaced earlier indigenous trade goods; but it didn’t really change the basic lifestyle of the people. However, the fur trade did bring other changes.

One of these was a change in the population. Many of the traders intermarried with the Indigenous people of the area. By the time of the 1870 census, their mixed-ancestry descendants accounted for almost 10,000 of the 11,405 residents of the new province. This group, in particular the Métis of French/Indigenous parentage, saw themselves as a New Nation and carved out an important niche in the fur trade as middlemen, interpreters, guides, and expert buffalo hunters. At the height of the fur trade, this became a thriving occupation.

The population around the junction of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers also had changed in the early 1800s when Lord Selkirk brought in crofters from the highlands of Scotland to farm and provide local agricultural products. The Red River Settlement by this time became the main transfer point where furs from the north-west were exchanged for food and other supplies. But the main food supply the traders sought was pemmican. The same portable and highly nutritious food that had sustained Indigenous hunters also fueled the canoe brigades. The Red River settlement became known as the ‘larder of the fur trade’.

The buffalo range was south of the lakes and west of the Red River— which includes this part of the country—Métis buffalo hunters became the main suppliers. By then, introduction of the horse and rifle had made the hunt more lethal than early bow and arrow days. To give an idea of volume of the trade, in 1852 the yield of buffalo products was tallied at well over one million pounds. During the semi-annual spring and fall hunts, this Trail must have turned from a back road into a busy highway.

By then, the Métis had at least a seasonal presence in this area. As early as 1837, the first local baptism was recorded. And in 1867, one of the most colourful local characters, John Francis Grant, came up the Trail from Montana with his herd of cattle and prize horses. Grant was the son of a western HBC agent and Métis mother. He built up a thriving ranching operation in Montana—until with the western flow of American settlers, the area got too crowded—and he headed up the Trail to what was soon to become the province of Manitoba. He started a ranch, build a mill and a large house, planted the first grain in the area— just east of here.

Historians still debate the extent of other Métis settlements in our area but histories of what is now the St. Daniel District record that, in 1866, a school was built northwest of the present town of Carman and that, about 1869–1870, a chapel was established at what was then known as Rivière aux Îlets-de-Bois. This was the first permanent settlement in the area. Which is why it is the other important historic site that we are recognizing this year by installing signs to mark the site.

By 1870, the fur trade era was passing—European demand for furs began to dwindle. With growing competition from American fur-trading posts and free traders, the HBC couldn’t maintain its trade monopoly. In 1867, the four eastern provinces entered into Confederation. A priority with John A. Macdonald’s government was to bring the western territory into the fold. They feared Americans settlers who were flooding westward would outflank the sparse Canadian settlements, lay claim to the Western Prairies, and cut Canada off from the Western ocean. Also Ontario was beginning to run out of arable land. Macdonald moved quickly to negotiate with Britain and, essentially, to buy out the HBC trade monopoly. By 1870, the government was ready to send surveyors to map out the new province for settlement.

At the heart of our 1870 Manitoba history, of course, is the story of how Louis Riel set up a Provisional Government and stopped the survey party. He did so in an attempt to get a say in the transfer process for the several thousand people already living in the area. He wanted in particular to ensure protection for land claims and for denominational schools, religious and language rights of what had become the largest local group, the French/Catholic residents of the area. This is a chapter of our history that has been revisited and rewritten, certainly since our early school day histories. One we should maybe all plan on revisiting in 2020.

Meanwhile, back here on the Trail, the local scene already was changing. In April, 1871, Samuel Kennedy, a volunteer with the Red River Expedition, arrived just here where the trail crosses the river, to claim the first homestead in the area as a bounty for his military service. If we had been here then, we would have heard the sound of axes and the crash of falling trees as he began to clear the land and build a log cabin. And we might have heard harsh exchanges with local Métis who accepted the Indigenous view that land didn’t belong to anyone, it and its resources were placed here for everyone to use. We might also have heard Samuel Kennedy proclaim that the Rivière aux Îlets-de-Bois was now to be known as the Boyne River, in tribute to his Irish Protestant roots.

Land claims became central to politics of the time – and, as you know, they are still with us today. The Manitoba Land Act allocated 1.4 million acres of land to children of mixed ancestry. The Métis leaders laid out claims to blocks of land, hoping to consolidate the population. One of several claims was to a broad swath of land two miles on each side of the river from the escarpment to the Great Marsh.

However, as land claims discussions dragged on, the land was rapidly being staked out for settlement. Eventually, Métis claims to this local block of land and others were abandoned. Much of the Métis scrip—individual certificates of land entitlement—was sold on to land speculators or other settlers. John Francis Grant was awarded a 240 acre homestead. He found that his open ranch land was now being fenced off by homesteaders. Some of his family settled at Îlets-de-Bois. Grant, along with many other disgruntled claimants, left for the still open lands to the West.

So, yes, the first homesteaders did come down the Missouri Trail. But, as we’ve seen, the Trail already had a long history. If you’ve read A.P. Stevenson’s account of the trail, you know it wasn’t any easy way for settlers to bring in their worldly goods from the East:

“ .. In the spring of 1874, in company with five others with ox and cart to carry provisions, I started to Pembina Mountain to look for land. The old Missouri trail was followed between Headingly and La Salle River near Starbuck. Nearly two-thirds of the way was through swamps, with water two or three feet deep. The ox and carts were mired three or four times, and what a delightful time we greenhorns had, up to the waist in water, with millions of mosquitoes adding their notes to the proceedings. It was a hungry, tired crowd that camped that night on the dry banks of the high-smelling La Salle, trying to dry socks, etc. Our clothing had early in the day been made up into bundles and tied high and dry on our backs during passage of the swamps. The following morning we found our ox had broken loose and taken the road to the Boyne River, so we started on foot for the same place. The distance was 30 miles, a dead level plain, without a tree, shrub or twig, no house of any description, not a drop of water to drink.” (Farmer’s Advocate, Jan. 4, 1911).

Within a decade, a rail line was built to End-of-Line (Barnsley), which became the new entry point for homesteaders. By 1901, the noisy creak of the Red River carts had given way to the mournful wail of the steam locomotive chugging its way through Homewood and Carman and westward through the escarpment, paving the way for small settlements at Graysville, Stephenfield, Roseisle and points west. Historian Alan B. McCullough who grew up on a farm where the Îlets-de-Bois cemetery and cairn are located points out that “by 1881 the settlement was an overwhelmingly Protestant, English speaking, agricultural community”(Manitoba History Number 67, Winter 2012: The Confrontations at Rivière aux Ilets-de-Bois).

By then, the local fur trade had collapsed, remaining buffalo herds and Indigenous hunters driven far to the south and west, and the early trade-based economy of the area was giving way to a market-driven agricultural economy. 1870 in effect marked the beginning of the end for the Trail. The land allocated to the Trail was eventually returned to landholders, is now cultivated to the point that even aerial infra-red photos shown no trace of what was once the lifeline the area in the pre-1870 era.

Long after it passes, history lives on in our symbols. Over the past couple of months, we’ve been become increasingly aware of how complex and potent these symbols—such as monuments or signs—can be can be in remembering our past. We have chosen to commemorate 1870 by unveiling this plaque and installing ‘historic site’ signs for the Îlets-de-Bois cairn as a reminder to our generation and those to come of both the richness and the depth of our local heritage.” *

Unveiling. Reeve George Gray and committee member Nikki Falk unveiled the Missouri Trail sign.

Their introductions explain why they were chosen for the honour:

George Gray. In many ways, George Gray is a living symbol of our pre- and post-1870 heritage. Through his great-grandmother, George has proud roots among our early Indigenous people; he also had ancestors with the HBC at the height of the fur trade, a teacher at the Red River settlement, and clerk to the Council of Assiniboia. In 1874, his great-grandmother Ann Smith laid homestead claim to the SE ¼ of 25-6-6w with her grant of metis scrip. Great-grandfather George Gray Sr. (also known as “Boss”) brought his family down the Trail from Headingley to the homestead where George still resides and where the local community of Graysville carries the family name. More than a decade ago, George along with Nedra Burnett, helped revive our then-dormant advisory committee. He served as RM Council representative on our committee until he became Reeve and he was one of our most diligent activists towards getting the Missouri Trail sign restored.

Nikki Falk represents our post-1870 heritage. Her great-great-grandmother, Margaret McCullough, was a sister-in-law of Samuel Kennedy and a relative of many of the early families still living in the area. In 1874, Margaret and her children travelled from Ontario to join her husband on their new homestead just west of here. Unfortunately, she contracted typhoid fever. In the midst of this current pandemic, we can only imagine the fear caused by this disease, at a time before health care facilities were available. A doctor was brought out from Winnipeg but Margaret and her 11-year-old daughter Martha died. They were buried just west of where the Trail crossed the river, in the now-abandoned Kennedy burial site (see Carman/Dufferin Cemeteries – A Guide To The Location, History, Art & Craft Of Local Cemeteries, p. 111).

The program closed with singing of ‘O Canada’, led by Shirley Snider and Elaine Owen.

*Acknowledgements. This is one instance where it has taken a community to raise a sign. Among the many people and organizations that made the event possible were:

Dufferin Historical Society – now the Dufferin Historical Museum Committee – put up the first impressive wooden sign on the site in 1961;

Judie Duthie and Vince Sotherand, landowners, enthusiastically supported the project and worked with us to preserve this important part of our local heritage for future generations;

Debbie Nicolajsen worked diligently during the past couple of years to bring together all the final pieces of this project. She also has compiled a file of articles and other research on the Missouri trail;

Lee & Lee Law Firm donated their legal services and expertise to ensure that this time the sign remains in place and is accessible to the public;

Sperling Industries generously donated the metal framing;

Sean Billing from Carman Granite crafted the sign;

Doyle’s Funeral Home supplied the sound system so we could be heard above the wind and traffic;

The flags were loaned from Carman Legion #18 and the Museum; Elaine Owen kindly provided the Métis flag;

Bev MacLean took great photos of the ceremony; and

The project was jointly funded by the Councils of the Town of Carman and the RM of Dufferin—represented on C/D MHAC by Councillors Bernie Townsend and Barrie Fraser.

Post-script. It was a bit of a ‘goose-bump’ moment when we realized how closely some of our own life stories had intersected on the Missouri Trail. In 1874, George Gray’s great-grandmother, Ann Smith, laid claim to her homestead in the Graysville area. It was the same year, 1874, that Nikki’s Falk’s great-great grandmother, Margaret McCullough, brought her family west to their new homestead. She would have stopped to visit her sister at the Samuel Kennedy home, where the Trail crosses the river. It also was in the summer of 1874 that my grandfather, George Leary, walked down the Trail on his way to homestead at Nelsonville. All of them would have laid foot on this same part of the Trail where we were meeting for our unveiling ceremony.

In recent years, our lives have intersected through a mutual interest in local heritage. Now, almost 150 years after our ancestors passed here on their journeys, we were meeting to preserve a significant part of local heritage—and of our own life stories—for generations to come. We felt sure, if those ancestors were looking down and watching as we unveiled the Missouri Trail sign, they were smiling and giving us a ‘thumbs-up’.