Fur Trade. Back in February, we identified the lengthy conflict between Britain, France, and their colonies in North America as one of the underlying factors in local 1870 events and noted that underlying issues of religion, culture, language, imperial expansion and trade were closely intertwined in the conflicts. In the West, these differences played out in rivalry around the fur trade.

For some three centuries prior to 1870, the fur trade remained the core industry in the West. It also became the main reason for settlement around the Forks and along the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. The key players during this time were early explorers/traders out of New France, the rival Hudson’s Bay and North West Companies, and the Indigenous trappers, hunters and middlemen who supplied the pelts and hides and food (pemmican) that sustained the trade.

In the century and a half between the founding of New France and the defeat of the French colony by the English, explorers and traders extended their activities westward into the heart of the continent and the Northwest. They returned with rich northern furs and with heightened interest in the interior as a target for expanding trade and spreading the Catholic faith. Fur traders from New France were soon making the annual voyage westward. They traded with their Huron allies along the Ottawa River and Georgian Bay, then travelled westward near what later became the Canada-U.S.A. border. Their canoes were laden with supplies and trade goods on the voyage west and with furs on return a year later.

Two of the more adventurous of these explorers/traders, Radisson and Groseilliers, left their party and ventured northward to the head of Lake Superior and beyond. They returned to New France with furs and plans for expansion into the North. Unfortunately, their employers didn’t share their enthusiasm for the venture and disciplined the pair, so they took their plan to the English. The rest, as we never tire of saying, is history.

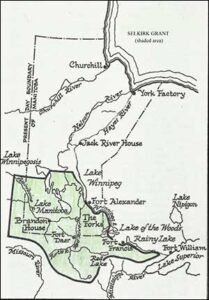

Rupertsland – the shaded area

Henry Hudson’s explorations for an ice-free Northwest Passage to the Far East had led to discovery of Hudson’s Bay and James Bay. These discoveries unintentionally opened up a shorter route to the fur-bearing lands that Radisson and Groseilliers hoped to exploit. A new trading company was formed under the patronage of Prince Rupert, cousin of King Charles II of England and first governor of the company. On May 2, 1670, a Royal Charter granted the Hudson’s Bay Company exclusive trading and commercial rights in Rupertsland.

This was the name given to the vast lands draining into Hudson’s Bay, an area of 1.5 million square miles and over one-third the area of Canada today. The company held this monopoly for 200 years from 1670 to 1870. However, there was little provision for enforcement of the monopoly. And by ignoring the presence of Indigenous residents and assuming sovereignty over the territory, the charter also opened the way to later confrontation over land claims.

The HBC built forts and fur trading posts along the shores of James and Hudson bays. Indigenous trappers and middlemen brought their furs down the rivers to the posts along the coastline. Formation of the HBC opened the way for competition with traders using the longer canoe route from the East. The HBC also had the advantage of better quality English trade goods.

Through the Treaty of Paris in 1763, France lost most of her holdings in North America. Rather than removing fur trade competition in the West, this led to formation of a reorganized, more efficient fur trade competitor, the North West Company. The new company established a way station at the head of Lake Superior. Canoes brought supplies from the East and exchanged them for furs brought in from the Northwest. This move reduced the eastern leg of the voyage to three months rather than a year. The new company also provided the same quality trade goods as the HBC. It was reorganized internally and, because of its more northern focus, began to intercept trappers and middlemen on their way north to the HBC posts. The fur trade moved into a more highly competitive and conflict ridden era.

The HBC began to see a drop in furs delivered to the shoreline posts. They responded to building inland posts. Then in 1811, Lord Selkirk was inspired by a philanthropic urge to resettle crofters who had lost their holdings when landowners enclosed their lands and transitioned to sheep farming. This venture combined with the further inspiration that an agricultural settlement in the West could provide a local food supply and a place where HBC employees could settle and raise families. The result was the Red River Colony or Assiniboia which included the area around The Forks and much of the pemmican-producing territory west of the Red River.

The Forks had become a center for exchange of furs from the Northwest and for the supply of pemmican, the food staple for the fur trade. Conflict heightened over the new presence at the Forks and attempts by colony officials to regulate trade including export of pemmican. This culminated in the Battle of Seven Oaks (1816). The conflict between the North West Company and the HBC was resolved through union of the companies in 1821. By this time, however the fur trade was changing. Demand for furs from the European market had begun to decline. With the absence of any enforceable law in the area, free traders had begun a growing trade with the American companies which were pressing westward under the banner of Manifest Destiny and offering serious competition in the fur trade. By 1870, The HBC was open to moving out of the fur trade.

Assiniboia – Red River Colony

Like most histories of the fur trade, this brief overview focuses on the trading companies, the Red River settlers and the growing pressures westward of US expansion. As our noted Manitoba historian, Gerald Friesen, points out, the traditional European-centered focus misses a facet of the story without which there wouldn’t have been any trade—the role of the Indigenous population. Rather than being passive recipients of trade, these were the folks who trapped and hunted and sustained the traders by providing the staple food supplies. Next month we’ll look at the people who lived here and who made the trade possible and how it affected their lives.

Note: To flesh out this bare-bones outline and get more background information on any particular topic such as the role of the coureur-de-bois/voyageurs, Battle of Seven Oaks, or early fur companies, you might find it useful to first check out these individual topics on Wikipedia and follow up with other online articles as your interest directs you. When you are able to access libraries, for a readable and perceptive history of the Prairies, try Gerald Friesen’s The Canadian Prairies: A History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987).