April 21, 2023

Finally, in recognition of Earth Day and in respect for Indigenous views of Nature, we’ll leave you with this Apache Blessing:

May the SUN bring you new energy by day

May the MOON softly restore you by night

May the RAIN wash away your worries

May the BREEZE bring new strength to your being

May you walk through the world and

Know its BEAUTY all the days of your life.

January 2023

Natural History. If you had to choose one word to describe the first month of 2023, it could be ‘white’. A pattern of unusual weather conditions brought a lengthy spell of morning fog. Freezing fog droplets resulted in both treacherous driving conditions and hauntingly beautiful coatings of rime on trees and vegetation.

The white landscape also made it even more difficult to spot some of our local animals. Most local animals adapt to winter by growing heavier coats or hibernating, others like rabbits or weasels very cleverly adapt by changing the colour of their coats. One of our local nature photographers, Lynette Stow, captured these delightful photos of a weasel enjoying the snow.

Local skiers have been just as excited as our furry friends over the quantity and quality of this year’s snow cover. Some no doubt ended up in the same poses as our little weasel.

Hopefully everyone has a few fond memories of this winter that they can record in their own life stories for the pleasure of generations to come.

June 2022

Natural History. Has summer finally arrived? The ducks are still swimming merrily about in that front yard pond, except that now the females are less often in sight. In this recent photo, the ‘men’, having done their ‘progenitive duty’ for the season, are hanging out together down at The Pond. The ‘ladies’ no doubt are busy keeping the eggs warm back on the nest.

Meanwhile, the plant kingdom is bursting forth with new growth and sweet-scented blossoms.

Native ferns beginning to unfurl

The ornamental crabapple – welcome for its beauty

and sweet scent

We are fortunate to have four separate seasons, each with its own sights, sounds, and scents and each with its own special beauty.

May 2022

Where’s Spring? This year Manitoba saw one of the top half-dozen heaviest snow falls since records were kept. A single day in April recorded twice the average precipitation for the month. Temperatures over the past month have been running around 15° below normal for this time of year. Now the month of May is being ushered in with local flooding, closed roadways and evacuation alerts. Mother Nature hasn’t done much to brighten the spirits of folks who are still grizzling away about their neighbours’ views on pandemic restrictions.

In the midst of this doom and gloom, a recent random act of kindness stuck out like a bright ray of sunshine. We were just digging out from that last big dump of snow, when a phone call came from someone we knew by sight and by reputation through heritage activities. The caller said she would be in the area—would it be alright to pass by and drop something off? This Good Samaritan drove bravely up the slushy, muddy lane and arrived at the door with a jar of homemade soup, muffins and – a big bouquet of soft, fuzzy pussy willows. “The pussy willows,” she said, “are a sign of hope.”

Sign of hope that Spring is coming?I figure this is the closest you can come to getting a ‘warm fuzzy’. These are the moments we’ll remember long after the snow has gone.

July 2022

A blanket is added (to the horse,

not the human) when the insects are

really bad

Natural History. This past couple of weeks have seen our ponds start to dry up. Unfortunately, the resident ducks have been replaced by an onslaught of mosquitoes. One small advantage of recent drought years was that we haven’t been plagued by these pesky insects for the past 2–3 years. As we see in this photo, both people and animals are finding ways to enjoy the outdoors in spite of the little pests.

We just received a report and picture of the rare local sighting of a pink lady slipper. This member of the orchid family is said to be native to the area. As we learn from this life story excerpt, pink lady slippers once grew in abundance in certain parts of the municipality:

A rare pink lady slipper

There was one area we kids trekked to each June to marvel at a large expanse of these beautiful flowers. We didn’t pick them and always kept the location pretty much secret. Years later, I took [my husband] to share the magic of this secret place. We found that the trees had been cut, the land was under cultivation and there was no longer a trace of pink lady slippers. It is one of the saddest memories I have of the past. So you can imagine our excitement a few years ago when the grandkids spotted a couple of the flowers when they were here for a family gathering. They were the first I had seen for almost 60 years. It was a special treat for family members who had only heard of these beauties from my stories.

But the real significance of the pink lady-slippers for our family goes way back to the 1930s and the Great Depression. Our mother’s grandmother died and Mom was very upset that she couldn’t afford to buy flowers for the funeral. Dad said, ‘Don’t worry—I have an idea.’ She knew she could trust him to come up with something creative. On the way to the funeral, Dad stopped the car, disappeared down a slope into a gully and came back with a small spray of pink lady-slippers. They were pretty much the only flowers at the funeral, and they were given pride of place on the coffin. Being so beautiful and unique, they paid proper respect to a woman who was much beloved by both her family and the community—and one who prided herself in her own well-tended garden. That was one of our mother’s only positive memories of the Depression.

“The most treasured heirlooms are the memories of our family that we pass down to our children.” (Anon.)

August 2022

Natural history. Some of the most interesting ‘history-in-the-making’ events from the past summer have been happening in the world around us. Mother Nature has continued her wake-up calls with everything from thunderstorms and heavy rains to prolonged heat and humidity. Our August meeting was postponed when a tornado alert sounded just as we were leaving for Carman. Fortunately, a tornado didn’t materialize, but the storm did bring golf ball to baseball size hail to nearby areas.

Early morning beauty

One of the positive outcomes of Mother Nature’s rather extreme activity has been the opportunity it’s provided for some stunning photographs. Heat waves followed by cold fronts have brought heavy fog. Nikki Falk captured this striking image one morning on the family farm.

Monarch butterfly and Milkweed

Monarch butterfly. One of the more concerning environmental reports has been the declaration that monarch butterflies are now considered an endangered species in Canada. Monarchs are threatened by the effects of climate change, loss of the forest habitat where they overwinter in Mexico, and loss of the native plants such as milkweed, on which their survival depends. We likely all remember when farmers were actively using pesticides to eradicate milkweed from their crops and making sure that roadside ditches were carefully mowed to get rid of any stray plants. Their success combined with the erratic weather patterns of recent years have made annual migration hazardous and have brought these fascinating insects to the attention of environmentalists. The narrative is changing from one of eradication of milkweed to encouraging establishment of butterfly gardens that incorporate milkweed along with such flowers as goldenrod, black-eyed susan, asters and coneflowers.

One of the fascinating things about history—if you don’t agree with a trend, just wait a generation.

September 2022

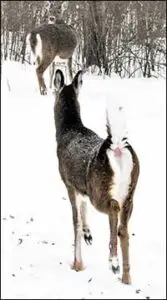

Natural history. Autumn colours have arrived in rather speedy fashion this year. After a couple of nights of frost, the leaves are turning from lush green to yellow and dry brown. Apples have taken on a ripe, pink blush and, to the delight of the deer, are beginning to fall to the ground. Even the deer’s coats have suddenly begun to change colour.

Speaking of nature, you never know what you might see while you’re watching Mother Nature busily making her seasonal changes. What would you think if you looked out the window and saw this in your back yard? If you guessed it’s the head of an elderly, decapitated sasquatch, you’d be wrong.

It is, in fact, the north end of a porcupine that’s going south. He even left a few quills on the deck as a calling card. Just hope he doesn’t chew up the cedar siding and walkway boards the way he did last time he visited the yard.

October 2022

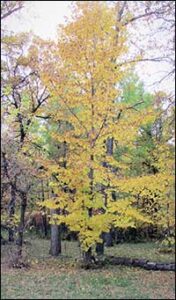

Basswood

September 30, 2022 [IB]

Wasp nest in basswood

October 3, 2022 [IB]

Natural History – Basswoods & Wasps. This year, autumn colours seemed to fade overnight. One day last week, strong gusts of wind blew in from the north-west, creating showers of swirling leaves; within a few short hours, trees were left looking cold and bare.

The basswood tree had been especially beautiful this year. Suddenly it was a skeleton of bare, grey-brown branches.

Along with disappointment came a surprise. The summer’s heavy growth of leaves had been hiding the wasp nest we had been trying to locate all summer. And it wasn’t just any wasp nest. This one was the size of a large football.

The nest is still in place, so we can’t show a dissected cross-section. But if you want to see what it would look like on the inside and learn a bit more about the wasps that have been busy pollinating our plants and swarming the hummingbird feeders over the past month or so, check out this link.

October 2020

Caroll McGill. We were all saddened this past month by the loss of Caroll McGill, one of our most dedicated long-time supporters of local heritage.

Caroll McGill at Wellness Fair

Caroll served for many years on the board of the Dufferin Historical Museum and was one of the most active volunteers in every local heritage event. She recently contributed a history of the fifth-generation McGill family to the Homesteads and Family Farms section of our website.

Caroll also was active in the community with organizations such as the Garden Club. One of her special interests was in native plants which she cultivated and tended in the Museum grounds.

This is one aspect of our heritage that we haven’t yet examined. What plants are indigenous to this region of Manitoba and how have they been used? We had just contacted Caroll this spring for guidance on researching native plants when COVID-19 brought our activities to a halt.

Although most of us are aware that plants and herbs played an important role in Indigenous healing and as part of seasonal diet, we are sadly short on specifics. We have slightly more information about wild fruits that early settlers gathered and plants they used for medicinal purposes. Over the next few months, we’ll be exploring this topic in more depth. Where possible, we’ll draw upon local sources of knowledge and experience. We are hoping one of our local plant enthusiasts will agree to help us on this journey. Two of the local resources we’ll be consulting are Caroll McGill’s notes from the Museum and a small volume titled “Wild Plants of Central North America for Food and Medicine“, written and illustrated by our late local Roseisle artist Stephen Jackson and Linda Prine, published in 1978 by Peguis Publishers.

We are pleased to dedicate this native plant series to the memory of our heritage colleague, Caroll McGill.

Our 1870 Heritage – Native plants. A feature of heritage that often escapes our attention is the impact of the socio-economic and cultural changes on the local environment. The current pandemic has focused attention on the outdoors and on home gardening. This, along with a growing concern over climate change, is reflected in growing interest in native or heritage plants. These are plants that grow naturally in an areas opposed to “exotics” that have been imported from other countries. “Indigenous” plants are native to a particular region.

Organizations such as the Canadian Wildlife Federation (CWF) and the Invasive Species Council of Manitoba (ISCM) are in the forefront of public education on the significance of native plants and on what not to plant. They point out that native plants are a product of the balance of nature that develops over time in a particular area or ecosystem. As such, they are part of our natural heritage. Heritage plants usually survive longer than non-native species and need less tending, because they are hardier and more disease resistant.

A concern with non-indigenous species is that they can become weeds in areas where they aren’t originally from, and can take over habitats. CWF notes that this in turn can “alter the whole ecosystem by not being the plant that species like birds or small mammals feed off, they can change ground water levels by taking up too much water, and they can cross pollinate with the indigenous species, creating hybrids.” For more information, visit the CWF site.

The ISCM provides a list of plants many of us have in our gardens that are not recommended for local planting. We are likely all familiar with invasive plant species such as leafy spurge that proliferate in our ditches and non-cultivated land.

Over the coming months we’ll be profiling some of our native plants that both Indigenous Peoples and early European settlers used for food and for healing. Our recent interest was sparked in part by stories of how early families used local plants in home remedies. We heard for example of a grandmother who healed a severe burn on her foot by using a salve of Balm of Gilead buds steeped in lard (News and Events, March 2018). Those buds, by the way, are the sticky black poplar buds that litter the ground and stick to your shoes each spring.

Please note that many plants may be harmful. Always seek advice from your health care provider before trying a plant for medicinal purposes.

It’s a bit late in the year to begin a series based on foraging for local plants. But there is one shrub that still stands out amongst the fast-disappearing fall foliage – the high bush cranberry.

Native Plants – High Bush Cranberry

High bush cranberries (Viburnum trilobum) are one of the wild fruits found in this region as well as other parts of Canada. Indigenous peoples added cranberries to pemmican; they also used them as a dye. From the time of the early settlers to the present day, high bush cranberries have been a local favourite for making jams, jellies and juice. You are unlikely to forget the rather unpleasant smell of boiling cranberries or the mouth-puckering taste of the ripe fruit which sweetens slightly after first frost.

This is an attractive shrub with maple-leaf shaped leaves. In spring it sports striking clusters of white flowers. Autumn leaves range from bright red to purple. As seen in the photo, the brilliant red berries can often be seen well after first snowfall, until they are gladly harvested by birds and animals.

High bush cranberries are high in vitamin C. Among its medicinal properties, the bark and leaves can be brewed in a tea for relief of pain and as a sedative. And, though it doesn’t qualify yet a heritage-status beverage, on a hot, muggy, summer day there’s nothing more refreshing than a chilled glass of cranberry juice and fizzy soft drink.

November 2020

Natural History. One helpful response to our new series on Heritage Plants is the suggestion that we expand it to look more generally at the natural history of the area. And that we draw upon the good folks in the community to share some of their favorite nature photos on the website. What a great idea, especially since the pandemic has us all outdoors more these days and everyone is getting top-quality photos with their phones or digital cameras.

We’ll also be trying to track the natural history of this area across past generations. In our review this year of our pre-1870 heritage, we looked very briefly at the lifestyle of Indigenous hunter/gatherers as they followed seasonal plants and animals. Buffalo herds served as a mainstay in the diet of both the Indigenous population and the canoe brigades of the north-western fur trade. By the time homesteaders arrived post-1870, the vast herds that roamed the area south of the lakes and west of the Red River had been decimated or migrated further to the southwest.

As with other parts of our history, most written records are from the post-1870 era. The early settlers continued to rely on hunting as a mainstay of their diet. (News & Events, October 2017).

By 1900, the local population was largely of European origin and knowledge of the pre-settlement era was fast fading. In 1900, the Dufferin Leader (1900-01-25) noted that:

A buffalo skull with the horns attached was picked up on the banks of the Boyne on Christmas day by one of our townsmen. This raises the query of how long has it been since buffalo made the prairie in this part of the province their feeding ground. It would be interesting to hear from some of our readers on this question.

Newspaper accounts from around this time also suggest a gradual change in focus towards hunting for ‘sport’ as well as survival. Reminder: if you haven’t already checked out this website, copies of both the early Dufferin Leaders and the Carman Standard can be found online through the Pembina Manitou Archive.

I.B. Werseen, of Roseisle, shot two elk near his home on Monday last. They were fine animals. Mr. Werseen says that as he has killed his allowance of deer, he will now turn his attention to bear. Last season he was lucky in securing the pelt of one weighing near 500 lbs. (Dufferin Leader 1899-12-07).

M.E. DeMill and M.J. Hemenway went out for a goose hunt on Monday and returned yesterday with a bag of 47 geese, two ducks and a sand hill crane. (Dufferin Leader 1900-04-26).

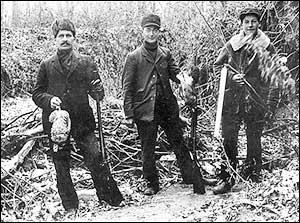

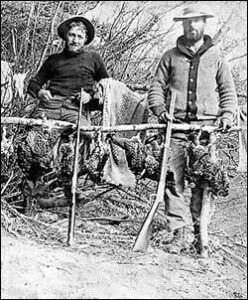

Prairie chickens’ were identified in the early newspapers as a prime source of food and sport, drawing hunters into the area from far afield. It’s difficult from available photos to confirm the identity of these birds, whether they were actually prairie chickens or the ruffed grouse that still frequent the area today.

Hunting prairie chicken (grouse?) ca. 1900 A present-day ruffed grouse

Whatever the species, they were the reason behind another ‘sporting’ venture:

This is the season when the prairie chickens are hatching and at present large numbers of them have congregated in the “Poplars ” northwest of here for breeding but the nests are being robbed of the eggs by crows almost as quickly as the chickens lay them. Crows are said to be there in thousands and a crow hunt was organized yesterday to make a raid on these pernicious thieves and exterminate as many of them as possible. Between forty and fifty of our local sportsmen agreed to join in the hunt. Mr. M.E. DeMill, who was one of the captains, being away from home, the hunt was called off until Arbor Day, when many others will be able to join in the sport. It is said the crows are doing more toward the extinction of these game birds than all sportsmen combined, and for this reason it is deemed advisable to wage a war against them. (Dufferin Leader 1900-04-26).

The crow shoot on Arbor Day resulted in a large bag of game, and the contest was won by M.E. DeMill’s party. The score stood 5,680 points for DeMill and 3,660 for Dr. Brown, giving the former a winning margin of 2,620 points. The scale of points were for crows 50, wolf 50, fox 50, hawk 20, owl 10, gopher 5, blackbird 1. There was no big game secured, but there was a large percentage of crows and gophers. The largest score was made by Mr. DeMill, who brought in 26 crows. The scores were counted in the Massey-Harris warerooms, and were viewed by very many on Saturday before they were carted away. The losing side put up the supper at the Starkey House. (Dufferin Leader 1900-05-10)

A few encounters were still being reported in which the animal population might have gained the upper hand:

The prairie wolves are becoming very wild with hunger, and last week a farmer north of Treherne had a little adventure with three of them. They jumped up repeatedly at his buggy and seemed very desirous of having a human supper. They are supposed to be a cross between the coyote and timber wolf, which accounts for their boldness. (Dufferin Leader 1900-05-31 from .—Treherne Times ).

In recent years, there have been reports of coyote/wolf crosses in the escarpment at the west end of Dufferin.

Coyotes – still part of our local natural history

Memories of Coyotes. Early newspaper accounts like those above give valuable insight into our past. One of their limitations is that, like other written histories, they tend to report events and dates but are less likely to enlighten us on the thoughts and feelings of the people involved. That is one reason we are so keen on organizing our life-story workshops.

What can life stories tell us about our natural history that isn’t covered better in newspapers, histories and other textbooks? Perhaps most important is the insight it gives us into the relationship between people and their environment. The best way to illustrate this is through the stories themselves. Here, by permission of our life-story workshop leader, retired veterinarian Lynette (Leary) Stow, are memories she wrote several years ago about growing up and later returning to the family home where she now lives and where coyotes are still an integral part of the natural environment.

A Light in the Darkness

When I awoke this morning, the entire sky was the deep purple-blue of a bruise. I was certain we were in for some weather, as Dad used to say. The southwest wind was stiff but still warm. I slipped my runners on over bare feet and went outside, still in my pyjamas and robe. The goldfinches and chickadees were crowding into the feeders, jostling each other and stuffing themselves with sunflower seeds while they had the chance. I wandered around the yard, sipping my hot coffee and enjoying the fresh crispness of the air. I was reluctant to leave the peace of it all, but eventually I was chilled enough to concede.

By the time I had finished my second cup of coffee, the sky had faded to a dull grey, but the temperature was dropping. The day grew steadily cooler and the wind stronger. By dusk the wind had turned cold and was howling like a wild thing around the windows. It reminded me of the coyotes. Last night they were singing to each other from all areas of the valley. They welcomed the darkness with their cries and called each other together before they trotted off to hunt. Faint, tinny yips from distant points were answered by powerful, quavering howls from just across the river. Standing in the dark yard tonight with no moon overhead and the wind howling through the trees, I felt the night like a living presence. The coyotes were part of the night, but I was weak and alien. I stood rooted to the ground, deafened and unnerved by the wind, the skin on my arms prickling. I was like a deer that could sense the predator but didn’t know which way to run. The dog felt it too, standing stiffly and staring out into the blackness. I scooped him up in my arms and retreated to the light and warmth of the house.

Now, sitting comfortably in my rocking chair with the wind and night locked outside, I remember another night like this long ago. I was walking with Dad, getting some fresh air before bed. The wind hid all the usual night sounds and I felt exposed, vulnerable. I pulled in close beside Dad and when our feet were crunching the gravel in unison, and I could smell the cigarette he held cupped in his hand, I was immediately safe. It was as though he carried a light with him. To him the night was a friendly creature, as comfortable and familiar as the faded quilt on his bed.

Dad has been gone five years now; that warm circle around him is gone too. The world seems less predictable, less kindly and safe. It would be easier to turn my back on this place than to discover the security and peace he had here. But I will not. His soul was complete when he was at home in his valley. He understood and trusted it. He celebrated his joys in it and buried his sorrows here. I will also. I will walk the hills and trails, explore the hidden places.

I will celebrate and mourn here. Someday, I will stand in the dark, beyond the reach of the yard light and listen to the coyotes sing. I will wrap the comfort and familiarity of it around me like an old soft quilt. I will carry my own light — Lynette Stow

December 2020

Natural History. In November, we looked at a few newspaper items that spoke to the interaction between the early settlers and local wildlife. As in later years, sports were then a major feature of the weekly news. In the days before more organized team sports such as hockey or curling dominated the press, emphasis was on hunting as an outlet for the competitive side of mankind. This even applied to holidays.

Local hunters early 1900s (Coleman Collection)

Wild Birds. Arbor Day was a day not only to plant trees, it also featured a ‘crow shoot’. “The crow shoot on Arbor Day resulted in a large bag of game, and the contest was won by M. E. DeMill’s party. The score stood 5,650 points for DeMill and 3,630 for Dr. Brown, giving the former a winning margin of 2,020 points. The scale of points were for crows 50, wolf 50, fox 50, hawk 20, owl 10, gopher 5, blackbird 1. There was no big game secured, but there was a large percentage of crows and gophers. The largest score was made by Mr. DeMill, who brought in 26 crows. The scores were counted in the Massey-Harris storerooms, and were viewed by very many on Saturday before they were carted away. The losing side put up the supper at the Starkey House.” (Dufferin Leader 1900-05-10).

(If you haven’t already checked out this website, copies of both the early Dufferin Leaders and the Carman Standard can be found online through the Pembina Manitou Archive.)

And on Thanksgiving Day, why not give thanks for a fine harvest by holding a turkey shoot? “A shooting match for turkeys was held in the fields south of town on Thanksgiving Day. Quite a number of the sports were present, and some very good shooting was done. The weather, however, was a little too chilly to be enjoyable.” (Dufferin Leader 1910-11-03).

In the west end of Dufferin, a local lodge made a full day of it. The Dufferin Leader (1910-10-27) announced that: “Loyal Orange Lodge No. 2137 Roseisle, will give a Grand Ball on the evening of Friday, Nov. 4. On the afternoon of the same day a Turkey Shoot will be held. Admission to ball, $1. Come and bring your girl.”

Picture young ladies adorned in their finery, while the young men had a quick wash up and change of clothing before hitching up the horse and buggy to head for the dance. What do you think the main topic of conversation was at the Grand Ball?

Wild turkeys are a native North American bird. Although sources seem to differ on whether the range of certain subspecies included Southern Manitoba, these tales of early turkey shoots seem to confirm their presence in the area. Hunting took its toll, and it was as recent as 1958 that wild turkeys were reintroduced to the area near Miami, Manitoba. They have since proliferated and are now both highly visible locally and a prime target during the autumn hunting season. The photos below are of recent vintage – taken of turkeys released in the wild over the past several years.

Wild tom turkey struts his stuff

Wild turkeys – A tom turkey herds his flock of females across a local roadway.

In early years, the all-out assault on game birds soon included many outside hunters and brought a reaction from the press and local public. The Carman Standard (1890-09-18) reported that “Over 600 chickens have been slaughtered in this neighborhood by Winnipeg and Yankee hunters, and, as a consequence, the hunting for this season and next has been entirely ruined.” At a “mass meeting” held at Dufferin Hall, a resolution passed calling on the Provincial government to regulate hunting in the municipality. The resolution stated that “Whereas the game birds of this municipality are now wantonly and wastefully being destroyed, mainly by persons who are non-residents of this district, many of whom are aliens to our country”, these persons should be asked to “desist from further destruction of game” in the present season. Farmers should consider prosecuting trespassers and livery stables and others cease hiring out horses, carriages or other vehicles to transport hunters to hunting areas. This backlash against indiscriminate hunting led to appointment of ‘game guardians’ and introduction of hunting licences.

The arrival of settlers affected wildlife in ways other than hunting. An item in an early Dufferin Leader (1903-04-13) noted the effect on the flight patterns of birds: “Wild geese are almost a thing of the past in this locality. Since the drainage of the Boyne Marsh they have changed their course of flight.” A century later, most of the small sloughs that dotted local farmlands also have vanished. Dufferin waterfowl now congregate on the man-made lake at Stephenfield Provincial Park where large flocks have recently been scouring nearby harvested fields for the last pickings of grain before heading south for the winter.

Canada Geese – time to head south

Animal Wildlife. It wasn’t just wildfowl that were threatened by overhunting. We have already seen how, in the earlier pre-1870 era, demand for pemmican as food the western fur traders led to disappearance of buffalo in this part of Manitoba.

Other animal species besides buffalo were soon in decline. Pre-1900 newspapers and life stories from that era speak of elk in this area of Manitoba. We noted in the November update that a Dufferin resident had shot two elk near his home. Ethel Chisholm’s parents homesteaded two miles west of the present-day hamlet of Roseisle. She recalled that “There were numerous bears and elk in the hills at Roseisle….Elk could be seen on the top of Mt. Ararat from the doorway of Smith’s home” (The Rural Municipality of Dufferin 1880-1980, p. 70). ‘Mt. Ararat’ as it was then called was part of what was later known as ‘Snow Valley’ ski resort.

And then there were Tom Ticknor’s tame elk. In earlier days when Dufferin extended as far south as the Nelsonville, Ticknor was one of the colourful characters in the district – an early settler who wore a buckskin jacket and wolf tail cap, and drove a harnessed team of elk. He tamed elk calves and built up a herd in the area west of Miami. When he died in 1889, his wife feared that hunters would destroy the herd and they were shipped west to a new home at Banff (Pembina Country – Land of Promise 1974, pp. 58-60).

White-tailed Deer. Everyone is familiar with the herds of deer that visit local fields and bound unseen out of the ditches along roadways. Oddly, white-tail deer are not a native species in Manitoba. In the late 1800s, the arrival of settlers and introduction of agriculture provided a favourable habitat in southern Manitoba; deer migrated northward from their original home range south of the international border. The earliest account of white-tailed deer in Manitoba was in 1881 along the Red River near the border.

The presence of this species—now one our most common forms of wildlife—is another reminder that arrival post-1870 of waves of settlers permanently altered not only the socio-cultural and economic profile of the Province—it also had a profound impact on the natural history of our area. In the case of the white-tailed deer, this even applied to members of their extended family.

For more information and insight into this species go to the Manitoba Fish and Wildlife fact sheet.

A quick look at their genealogy confirms that deer, moose and elk are all hoofed ruminant mammals belonging to the Cervidae family. Unfortunately, white-tail deer are asymptomatic carriers of a parasite that causes brain-worm. While it has no impact on the deer, brain-worm is deadly in moose. After their arrival in this region, white-tail deer soon began to displace their local cousins. For more information, go to a fact sheet on moose.

Aptly named white-tailed deer

Moose. There is evidence that at least some moose were present in the area during the early years of settlement. The Dufferin Leader (1901-06-06) reported that “Two moose were found in Alex McCullough’s pasture a mile west of town. They were lying resting in the shade of some trees and apparently had been grazing in the field until satisfied. After being startled by the approach of visitors they started off in an easy trot in the direction of town.”

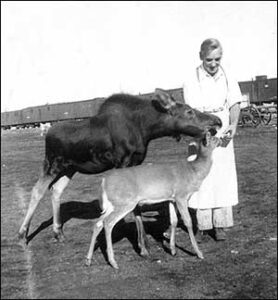

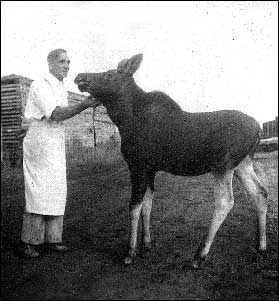

It seems that both the moose and the newly-arrived white-tail deer population appreciated the new cultivated crops. We can’t be sure from local histories just how rapidly the deer population spread however there are references to hunting ‘jumping deer’ in the district. Early 1900’s photos from the Garwood Collection show a Mr. Croome, a cook for the C.N.R. train gangs, with his pet moose and with both his moose and a tame deer.

David Croome with pet moose and deer (Garwood collection)

By the early 1900’s both elk and moose were disappearing. The Carman Standard (1908-11-26) reported that “Those monarchs of the forest, the elk and moose are not nearly as numerous as in the early years. They used to be fairly plentiful in the Pembina Mountains west of Carman, but incoming settlers have decimated them and driven them further away”.

Thanks to the parasite they carried, newly arrived white-tail deer population may have posed an even greater health hazard for their four-legged cousins.

There is no record of what became of the Croome animals. However, in recent years the return of moose to the area has again been short-lived as they succumbed to brain-worm. The only moose we’ve spotted this year is this bright and cheery Christmas decoration. It’s not the dainty reindeer ornament we usually see on lawns, but what could be more appropriate in this pandemic-ridden year than the image of this huge mammal that succumbed to a tiny parasite that it unknowingly picked up from asymptomatic carriers? Could there be a more apt reminder of why we are in lockdown this holiday season in an attempt to combat the COVID-19 virus?

April 2023

The Natural Environment – Then & Now. An earlier Carman Dufferin Leader (1898-05-12) waxed eloquent about the community’s natural setting:

The visitor who in the lovely Manitoba summer days, stops at the town of Carman, romantically nestling in the encircling windings of the River Boyne and sheltered by its bordering fringe of stately virgin oaks, is heard to remark “Why, what a lovely spot.” For beauty of situation Carman is not excelled by any other town in the province. Sheltered and embowered by a magnificent belt of oak, ash, maple, elm, bass wood and poplar, it is hard for a visitor who hails from a timbered country to realize that this is indeed a prairie town….It should be said for the originators of the town that their appreciation of the beautiful has preserved to us as far as possible the original trees, which gives to many of our streets the appearance of broad avenues, picturesquely lined with tall and stately trees. Here and there the visitor catches glimpses of beautiful vistas of river and woodland scenery, a worthy inspiration to either artist or writer. This feature has gained for our town a reputation of almost provincial note and it is becoming more widely known as a favorite resort for excursions and picnics.

Being situated only 57 miles by rail from Winnipeg, each summer finds a great number of Winnipeg citizens leaving their business and cares behind for a day’s outing to breathe the fresh pure air, enjoy the bright cheering sunshine, or promenade beneath the arched and embowered walks that abound on every hand of our fair town.

A couple of decades later the paper reported that “Miss Margaret Johnston, garden page and horticulture editor of the Manitoba Free Press…regards Carman as the most beautifully treed town she has seen in the province.” (Carman Dufferin Leader, 1926-06-10).

What is missing in these accounts is the reason these magnificent stands of trees formed an oasis in the midst of the open prairie grasslands, i.e., the existence of the river that threaded its way across the Carman/Dufferin area from the escarpment in the west to the Great Swamp in the east. It was aptly named the Rivière aux Îlets -de-Bois (“islands of wood”), later known as the Boyne River.

Our history of the river stresses its significance as the main source of water and, as such, as the lifeblood of the region. Over the centuries, Indigenous hunter-gatherers, Métis buffalo hunters and early settlers all relied on the river and its surroundings for water, shelter, fuel, and food. The Town of Carman grew up at this specific location largely because of the nearby water-driven Clendenning mill that ground grain and sawed lumber to build homes and businesses.

During the post-settlement years, the river also became known as a source for recreation. For many years, Carman’s Old Swimming Hole was the gathering spot for the community. In winter, swimming and boating gave way to skating.

Over the years, newspapers frequently pointed out the impact of a growing population on the water supply – pollution from using the river as a dumping ground for sewage, farm manure and garbage, as well as ongoing concerns about flooding and the need for dams and bridges. During these years, the community also began to show an interest and pride in beautifying gardens and home properties. Mayors such as S.J. Staples were noted for their efforts towards encouraging this trend by offering garden prizes, a practice that persists today.

In recent years, the community has rediscovered and begun to build upon these environmental assets. Groups such as the Boyne River Keepers (BRK) are leading the way in promoting the recreational potential of the river along with concern for water quality. They also have fostered a growing interest in the natural vegetation and wildlife along what has become the remaining wildlife corridor across the Carman/Dufferin municipalities. in recent years, the local Communities in Bloom (CIB) group has put the community even more firmly on the map with their colourful floral displays and pocket parks.

Thanks to the Stephenfield Park dam and water plant, the river now provides water for both the Town and R.M. and serves as a well-used recreation centre. As farms expanded and ponds and sloughs were drained, the river also has become a source of irrigation for agriculture and refuge for wildlife.

These observations carry significance in that they are being recorded on April 22, this year’s Earth Day.

June 2023

Natural History. We’ve had an interesting Spring season this year. Here’s a look back at a couple of Mother Nature’s special treats.

Plums are still among the more common wild fruits found in local bushlands.

Wild Plum Blossoms

When temperatures finally started to climb last month, a tell-tale cloud of white suddenly appeared among the newly greening trees. It will be a while yet before the fruits fully form and ripen to tasty, purple-red fullness. If you’re tempted to try them before they are dead-ripe, you’ll never forget their mouth-puckering sourness. We’ll be sure to check out these trees again this autumn.

Did you notice you were doing more coughing and sneezing and feeling more congested than usual this Spring? It could have been a reaction to oak tree pollen. Our wooden walkway had

Source of oak tree pollen

just been washed down earlier in the week, but, by the weekend, it was covered again by a fine green dust. The recent strong winds had brought with them a heavier than usual dusting of pollen from the oak trees. A-a-ch-o-o!

August 2023

Natural History. Any discussion of our natural environment these days will almost always involve some mention of the weather. Our ‘natural’ history has recently, in fact, been decidedly unnatural. Hot temperatures, severe localized storms, tornado and air quality alerts, and over 1000 wildfires burning across Canada. As a result, a number of scheduled events had to be postponed or cancelled One victim was the Boyne River Keepers’ (BRK’s) ceremony for naming of the trestle near their original dock on the Boyne River. We’ll look forward to having that news for you later this summer – weather permitting.

Photo credit: Ina Bramadat

November 2019

The Past Revisited? You can be sure the Dominion Land Agent didn’t hand out copies of the 1884 book “A Lady’s Life on a Farm in Manitoba” when he was singing the praises of life on the Prairies to potential Irish immigrants. The following is from page 78:

The cold is so great that you have to put on a buffalo coat, cap, and gloves, before you can touch the stove to light the fire…The snow on the prairie is never very deep, but it drifts a good deal, and was to the depth of twelve feet on the west side of the house.

On Thanksgiving weekend, we were hit with an unseasonable dump of wet, heavy snow that downed power lines, cut telephone service and blocked roads. Suddenly, we went from enjoying brilliant autumn leaves to whiteouts and immense snowdrifts. If, indeed, a picture is worth a thousand words, here is a 4,000 word summary of the event.

Day 1- October glory

Day 2 – Going…

Day 3 – Going…

Day 4 – Not going anywhere

Local Manitobans found themselves back in the days before hydro power, telephones, television and internet service, not to mention loss of hot and cold running water, refrigeration, and flush toilets. For those without power, this meant no electric appliances – no electric ovens, microwaves, dish washers, garage door openers – all those amenities people take for granted each day of their life.

How did people react to this experience? Although this area was pretty much shut down for up to four days, no casualties were reported. Most people had the good sense to stay put until the ploughs, tractors or snowmobiles arrived. Fortunately, outdoor temperatures remained around zero C; indoors without heat at around 12C.

In retrospect, it seems the main outcome of the storm was that everyone had a story to tell. People without backup supplies (generators, alternate heat sources, wells, bottled water, or lanterns) described how they managed without heat, water or warm food. Refrigerators and freezers were off and food began to spoil. Dusk falls early at this time of year, leaving families not just without television and computers but without light for reading. For some folks, ‘hardships’ were limited to having no hot coffee and no long, hot showers. A common theme among parents was that their children nearly drove them crazy because they had ‘nothing to do’ (no TV, video games, telephone). There didn’t seem to be a lot of sympathy for the fellow who told how he had to get to town for cigarettes, got badly stuck and ended up slogging some 3 miles home through heavy, wet snow.

In the midst of these stories, one question kept coming up – how on earth did our parents and grandparents survive back in the days before power, telephones and the like? Thinking back to childhood days, before hydro or telephones reached our little corner of the world, the simple reality was that we didn’t miss what we never had. This is one factor we often forget about when hearing or reading of the past – the importance of context. What was life like back then and how did it affect the way people coped when a storm hit?

There were some things every family had in common. We all heated our homes with wood which was still abundant on every farm in the area. Drinking water came from wells, was pumped by hand; and when ‘soft’ water froze in the rain barrel, we melted snow in a boiler on the cook-stove to do dishes, wash our hair or scrub the floors. If the roads were badly drifted in, everyone had a sleigh and a horse or two to get us through.

Early 1900s – winter travel with horses and sleigh [Photo: J.B. Coleman]

Then as now, there was no one story of how people coped with the arrival of snow. Our home, for example, had a Delco plant – gas-operated with battery storage. So we had lights and we had power to operate pumps that filled an indoor cistern and provided hot and cold running water. We also had central heating, fueled by a wood burning furnace. And there were no breaks in the supply of hot food, thanks to the kitchen cook-stove (and, of course, our mother). Most of our food was home-grown. We had at least a cow or two to provide dairy products and the makings for smoked ham. I recall one year counting 450 jars of preserves, jams, pickles, and meat that our mother had canned for the winter. We had a bin full of potatoes and root vegetables. A few staples such as flour, sugar and tea were purchased in bulk.

When the first big storm was on the way, my father and brothers made sure the farm animals were safely in the barn, watered and fed and that the wood box was full of wood. After supper, my brothers and I hauled out our skis and started waxing them. Snow meant we could ski to school. We lived in a valley and our one-room school was about a half mile distant up a winding trail near the top of the hill. Skis meant not having to plod through the snow. At recess we skied on the school-ground hills; at lunchtime and after school we buckled on our skis at the back door of the school and glided down through the trees almost to our own back door. We could laugh at those oft-told tales of how, in grandfather’s day, school-children walked three miles to school, through deep snow, uphill both ways.

But, recall that everyone had their own story. Several of our school-mates lived on top of the hill on the opposite side of the valley from the school. They also had a wood-heated home, but without the Delco plant and hot and cold running water. A large family, they didn’t have skis. To get to school, they walked about three miles – down one side of the valley, through our yard and up the long hill to the school. At the end of the school day, they trudged the same route back home. In other words, they walked some three miles to school and back, through the snow, and they did have to walk uphill both ways. Memories get reshaped over years of telling, but usually there’s at least a grain of truth.

Meanwhile, you have to wonder what, if anything, will be remembered a generation from now about our recent Thanksgiving weekend storm? Which of those stories will survive, how will they be reshaped over the years? Will anyone leave a written record as part of their life story? Writing personal accounts of the storm might be a fun warm-up exercise for participants in the life-story workshops C/D MHAC is introducing in 2020.